Financial Incentives Gone Wrong

And finally, we turn to perhaps the most common pitfall, the financial incentive. It is common in investment management to lower fixed annual fees in favor of performance-based compensation. On its face, this seems to be investor-friendly as it lowers the amount investors pay for average returns while rewarding exceptional performance. However, this practice is at the heart of many investors’ underperformance.

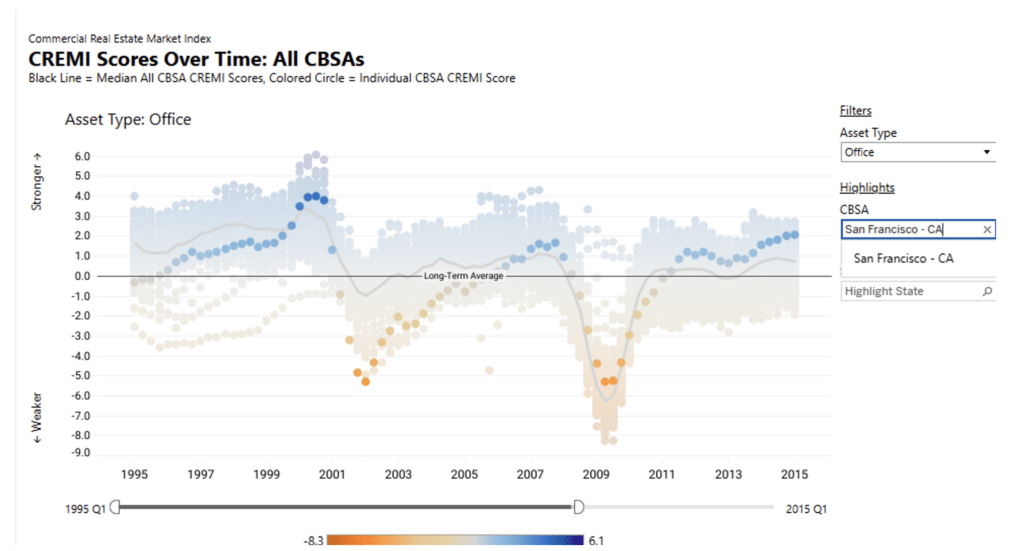

To set the stage for understanding this, we’ll look at the Commercial Real Estate Market Index (“CREMI”) published by the Atlanta Federal Reserve. This index highlights for various property types and geographies how a market performs relative to its long-term average and other markets in the US. In the two decades leading up to a hypothetical 2015 investment allocation, the Charlotte industrial market performed mostly at or below its long-term average for much of the period with weakness from the 2000 and 2008 recession recovering slowly and only roughly to long-term averages. Additionally, the Charlotte industrial market performed at or below the averages for all industrial markets in the US for most of that period.

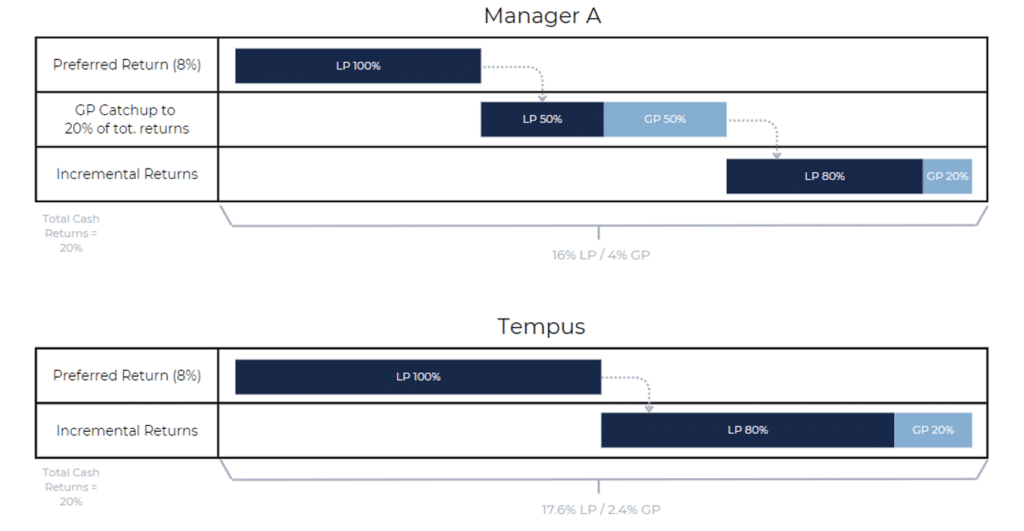

With this background, we now return to our manager selection. As with most investors, we chose a manager for our real estate allocation allowing them discretion as to where in the real estate market to deploy that capital. As is common for real estate managers, both managers’ fee structures borrow the carried interest provisions common in hedge funds. Accordingly, each manager’s investors will receive all returns on the investments net of fees paid until the investor receives an 8% annual return. Then for any returns above 8%, the investor would receive half of the incremental returns until such time as Manager A received 20% of the total returns from which point forward the investor would receive 80% and Manager A would receive 20%.

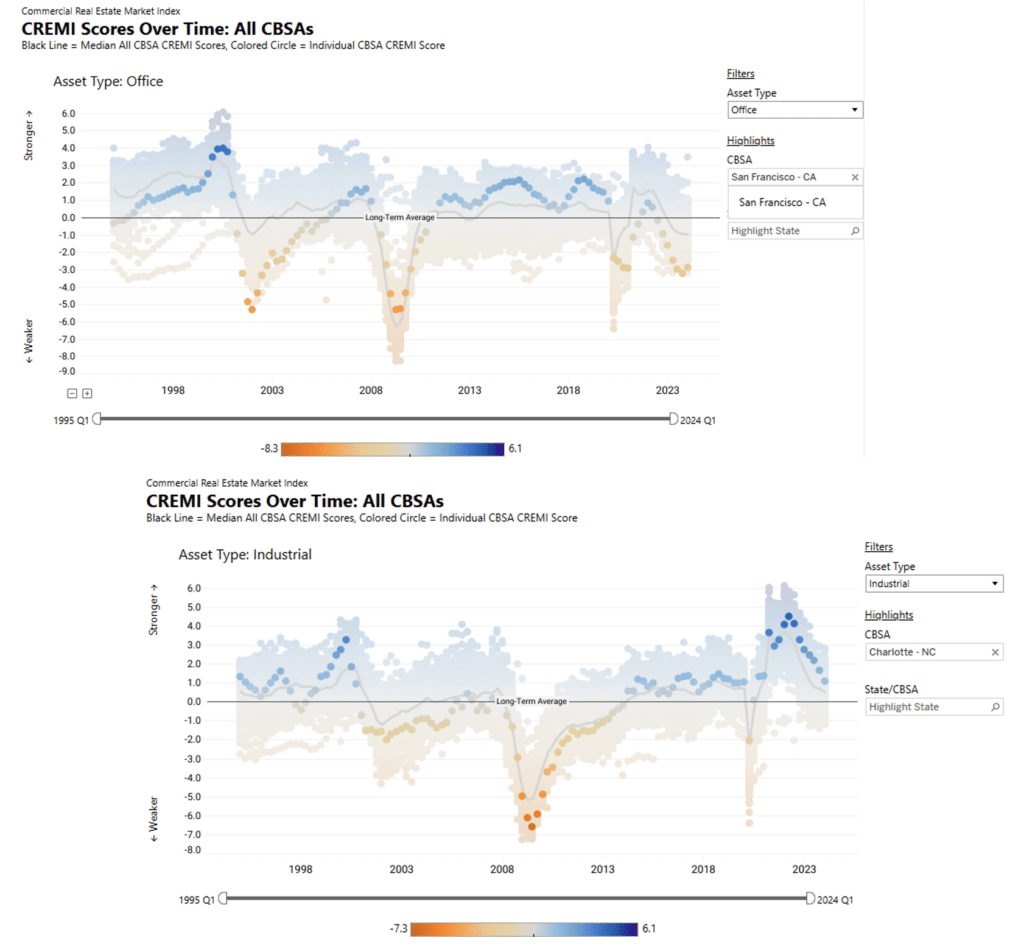

By providing incentives for returns above a fixed hurdle, managers are incentivized to focus on markets with higher volatility as the carried interest model provides greater reward for the manager when positive results are realized while yielding the same results to the manager (no carried interest) when negative results occur. For those investors that selected Manager A due to a lengthy history of higher returns, they missed the fact that they were allocating their portfolio to higher volatility (risk) to achieve those returns. Of course, that allocation decision had profound consequences as San Francisco office saw a sharp and potentially catastrophic downturn during the investment period. Meanwhile, the Charlotte industrial market shifted from its long-term trend of underperformance to an extended period of outperformance. We can see this divergence by expanding the timeframe of the CREMI charts.

Stay tuned for the final part of this blog series where we explore what investors really want.

Dan Andrews

CEO